In 1985 Mary Anne Warren first coined the term ‘gendercide’, a neologism that refers to gender selective mass killing. In India gendercide takes the form of ‘femicide’, the systematic destruction of females from birth through to middle-age, and the statistically abnormal female mortality is the result of foeticide, infanticide, neglect, violence, murder and suicide.

The scale of the killing of female infants alone defies belief. Figures from the 2011 census reveal that the birth gender ratio for children aged 0-6 now stands at 914 girls born for every 1000 boys, down from 927:1000 in 2001 and significantly lower than the global average of 935-950:1000 (estimates vary). The aggregate figure masks vast regional disparities. In Haryana, the state with the 4th highest GDP, the ratio is 830:1000. In contrast Bihar, one of India’s poorest states, at 933:1000 has a birth gender ratio that betters the national average. Aside from these extreme cases, large disparities are most evident in richer, better-educated, relatively urbanized areas and among the roll call of offending states are Maharashtra, Gujarat and Punjab.

If not aborted as foetuses, two mechanisms explain the high mortality of girl-children. First, where food, medicine and shelter are scarce, the ‘parity effect’ refers to the practice of favouring sons. If daughters aren’t abandoned, this neglect leads to higher mortality from stunting and susceptibility to illness. Second, decreased fertility rates (now 2.7 per family) have increased the demand for sons. Girl children tend to survive if they are the first-born or if a brother precedes them. The ‘intensification effect’ describes the fate of subsequent girl-children, whose mortality increases in the desperation to produce a son.

The dropping fertility rate is partially the result of improved female education and employment. Foeticide among the urban, educated and affluent is facilitated by the proliferation of technology, the falling cost of illegal screenings and disregard for laws criminalizing gender selective abortions. Modernisation therefore has not proved to be a panacea. Technology has expedited foeticide and, paradoxically, female empowerment has failed to eradicate the many social and cultural incentives to eliminate girl-children.

The host of social and cultural drivers include patriarchy, misogyny and the economics of marriage. Sons are heirs, of both the family name and estate, perform funerary rights and provide high returns on parental investments. Having been looked after and educated, sons provide a source of labour, income, a (bride-accompanied) dowry and when parents grow old they function as informal care systems. The opposite is the case for daughters. Custom dictates they leave the home and family upon marriage, and it is therefore the family gaining a bride that is the beneficiary of the costs of raising a daughter and amassing a dowry.

The policy imperative is self-evident. Comparisons between 2001 and 2011 census data show that widening birth gender ratios are creeping into newer areas. The tragedy of the mass elimination of women notwithstanding, the gender discrepancy gives rise to a number of damaging externalities. Violent and sexual crimes increase in populations with excess single young males, the shortage of marriageable women has increased human trafficking and sexual slavery (including minors), and has led to the establishment of a pan-south Asian bride buying industry. Men, unable to get married, now have higher suicide rates and perversely, rather than increasing the value and importance of women, their decreased number has tightened the patriarchal grip over their freedoms and sexuality. The urgency of the problem lies in the lag between normalizing the birth gender ratio and correcting these destructive consequences.

Culture and poor law enforcement are the obvious culprits, and in policy terms a supply and demand distinction is instructive.

On the supply side, factors that facilitate and enable gendercide include easily procured technology, cheap sex determinations and illegal abortions. Extensive legal prohibitions already exist. Sex determination tests were made illegal in 1994 (the PNDT Act was further strengthened in 2003), as was revealing the sex of the child in 1996. The fact that foeticide continues points to the need for more effective law enforcement, greater official accountability, swift punishment of offenders and stricter controls on access to technologies. Frustration with the official response, and cynicism towards the ‘soft’ NGO response, had led activists to take matters into their own hands. Networks of informers carrying out sting operations have led to the imprisonment of many mal-practising doctors. But over-enforcement or over-criminalization risks forcing gendercide underground, placing both mothers – who are often coerced – and children at greater risk.

As many commentators note, families determined enough to eliminate girls will always find a way. Supply side solutions therefore offer no guarantee that demand for gendercide – son preference, the economic logic of eliminating women and ritualism – would end. Gendercide is a practice in which men and women, of all ages, religions and socio-economic backgrounds are implicated. The policy challenge lies in effectively engaging with these diverse groups. Powerful efforts have been made to increase awareness, but combatting cultural norms is a no-guarantees, generational endeavor. Policy action is necessary immediately and South Korea demands attention as a success story.

In South Korea, high birth gender disparities have quickly been corrected, and the example highlights the importance of addressing underlying, macro causes. In addition to cultural crusades (the national ‘Love your Daughters’ media campaign) and regulating natal service providers, South Korea instituted a range of social service reforms. A three-pronged policy of improving education, changing the laws of inheritance and better welfare provision for the elderly removed many of the economic incentives for gendercide. In India attempts at reducing the costs of raising girl-children have been largely tokenistic: drop-off zones outside orphanages, tuition schemes and, in one case, presenting bicycles to families with newborn daughters. Addressing the causes of gendercide at a structural and societal level may be the missing piece of the policy puzzle. Unfortunately, India is a world leader in poor state service provision, and so optimism with India’s ability to replicate the South Korean example must be limited.

The article was commissioned by Oxford India Policy for a special series on India’s future policy challenges.

Ram Mashru is a freelance journalist and south Asia analyst. He specialises in the politics, human rights and international of India; and has had articles published in a number of national and international publications. He can be followed on twitter @RamMashru

The views expressed by guest contributors to the “It’s a Girl” blog represent the opinion of the individual author who contributes the content and should not be interpreted as being endorsed or approved by Shadowline Films. We feature these contributions to foster dialogue and exchange on gendercide and invite our readership to join the discussion.

We’re thrilled to announce that It’s a Girl will be available on iTunes and DVD next month. The release coincides with the anniversary of China’s brutal One Child Policy on September 25. Pre-orders will be available from September 10.

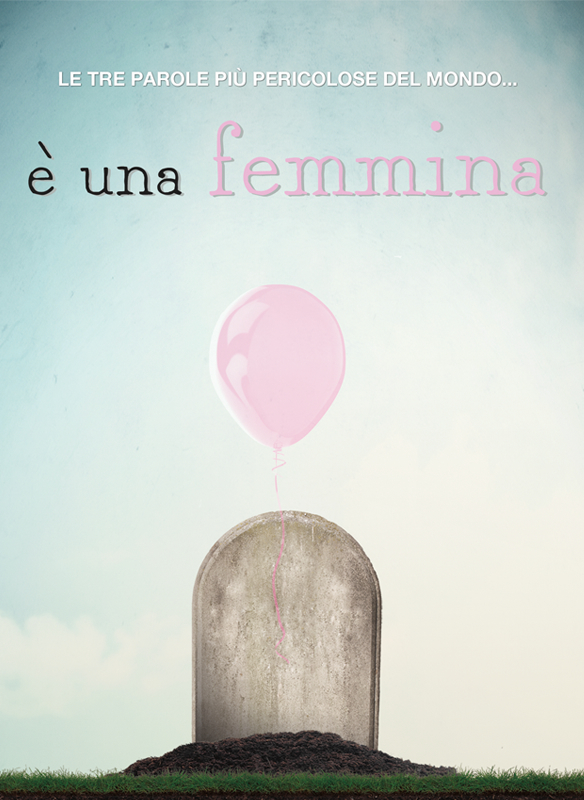

Since our initial launch, several groups have contacted us with a passion for expanding the reach of It’s a Girl into their own language group and have volunteered their time to translate the film into their heart language. As a result of their commitment to raising awareness about gendercide, we are thrilled to announce the availability of It’s a Girl in both Italian and Romanian. Both the Italian and Romanian premieres will be happening later this year.

Since our initial launch, several groups have contacted us with a passion for expanding the reach of It’s a Girl into their own language group and have volunteered their time to translate the film into their heart language. As a result of their commitment to raising awareness about gendercide, we are thrilled to announce the availability of It’s a Girl in both Italian and Romanian. Both the Italian and Romanian premieres will be happening later this year.