Why We Slept Through A Genocide—Part I

It’s a question that needs to be asked: How did the world sleep through this? In less than a century, more than 50 million women have been targeted simply for being female and wiped out from India. Millions have been killed before birth. Millions killed as infants. Millions killed as little girls. Thousands killed as new brides. Thousands killed as they are forced through repeated, back-to-back, unsafe abortions to get rid of girls. Thousands more killed for so-called “honor” or branded as “witches” and mob lynched. And many burnt alive as widows on the pyres of their husbands. Killed at every stage of life — simply for being female! There is no other human group in history that has been persecuted and annihilated on this scale. So, how did the world close its eyes to this?

I don’t ask this question lightly, for I have asked it of myself first. How could I, a woman born and raised in India, have remained blind to this all my life? It’s a question that caused me tremendous angst and put me through a year long process of soul-searching, and eventually culminated in my founding The 50 Million Missing in December 2006 – a global campaign to end the genocide.

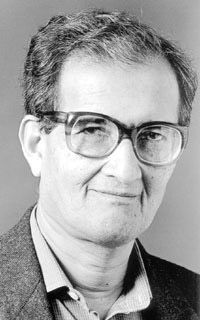

One of the incidents that my deliberation uncovered remains like a thorn in my soul, and I recount it here with much shame. It is an incident from my college days in the United States, and involves the Nobel Laureate, Dr. Amartya Sen, who had first used the term “missing” for the women who had been eliminated from India’s population. This is where the ‘Missing’ in my campaign’s title comes from. In 1986, Dr. Sen first raised the alarm on what his study revealed to be an abnormally high skewing of the normal, biological gender ratio in the populations of India and China. At that time he estimated that 37 million women who should have been a part of the populace of India, could not be accounted for. Despite that forewarning, the number of “missing” or eliminated females has continued to rise at an alarming rate.

One of the incidents that my deliberation uncovered remains like a thorn in my soul, and I recount it here with much shame. It is an incident from my college days in the United States, and involves the Nobel Laureate, Dr. Amartya Sen, who had first used the term “missing” for the women who had been eliminated from India’s population. This is where the ‘Missing’ in my campaign’s title comes from. In 1986, Dr. Sen first raised the alarm on what his study revealed to be an abnormally high skewing of the normal, biological gender ratio in the populations of India and China. At that time he estimated that 37 million women who should have been a part of the populace of India, could not be accounted for. Despite that forewarning, the number of “missing” or eliminated females has continued to rise at an alarming rate.

About four years after Dr. Sen’s news-breaking revelation, I had an opportunity to hear him speak. He was scheduled to give a seminar at a University in the Boston area, and my anthropology professor in the college I was attending, was keen to take our class to hear him speak. She urged us all to register, but since the seminar was on a Saturday, and most students (including me!) were not keen on giving up a holiday, she got a lukewarm response. She was disappointed but then had a brain-wave. She said, that after the seminar, we’d spend some time sightseeing Boston by night, and have dinner in China-town, before we drove back to the campus. She got a full class attendance!

This however, is not the worst part of my story! What I feel most embarrassed about, is that no matter how much I rack my memory, I cannot recall a word of what was said at Dr. Sen’s seminar. I was attending a women’s college then, which has strong liberal and feminist leanings. There are other such women’s colleges in the vicinity, some of whose students must have attended. Surely, someone must have raised the question of the ‘missing’ women? Not only do I have no recollections of that, but I am ashamed to say that I have a perfectly clear memory of what I had for dinner in China-town later that evening. It was Peking duck with plum sauce and mu-shu pan cakes.

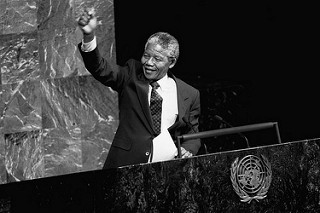

It is the understated implications of this incident that have haunted me. I keep thinking of possible parallels. What if I was, say for example, a black African person studying in the U.S. and had the chance to meet someone who had just published a book on the horrendous scale of violence inflicted on black people under apartheid in South Africa. Would I drag my feet on the chance to hear this person speak? Would I need to be given an ulterior incentive to do so? Would I later, draw a complete blank on what this person said or what was discussed at his talk? How would I have responded?

The ultimate irony of this story is that during this very time period, I was actually, actively involved in the student movement against South Africa’s apartheid government. Even before I had left India, at the age of 16, I had written an anti-apartheid poem that The Statesman newspaper in India had published. Soon after, I got my first passport and when I saw the stamp of the travel ban to South Africa on it, I had rejoiced that my government was not going to stand up for fascism. In college in the U.S., I eagerly attended talks by high-profile anti-apartheid leaders. I can still feel in my bones that highly charged energy and anger in the auditorium during a talk by Mark Mathabane. I spent weekends travelling overnight to attend public rallies in Washington D.C. and did not give a second thought to giving my time, energy, and concern to all other forms of anti-apartheid activism, including distributing flyers, and boycotting goods and companies sustaining the apartheid government.

The ultimate irony of this story is that during this very time period, I was actually, actively involved in the student movement against South Africa’s apartheid government. Even before I had left India, at the age of 16, I had written an anti-apartheid poem that The Statesman newspaper in India had published. Soon after, I got my first passport and when I saw the stamp of the travel ban to South Africa on it, I had rejoiced that my government was not going to stand up for fascism. In college in the U.S., I eagerly attended talks by high-profile anti-apartheid leaders. I can still feel in my bones that highly charged energy and anger in the auditorium during a talk by Mark Mathabane. I spent weekends travelling overnight to attend public rallies in Washington D.C. and did not give a second thought to giving my time, energy, and concern to all other forms of anti-apartheid activism, including distributing flyers, and boycotting goods and companies sustaining the apartheid government.

It is therefore painful, and bewildering, that I remained nonresponsive to the issue of the persecution – the systematic, mass-scale annihilation – of Indian women. Women like me!! And so, I had to first ask myself, before I could ask the world: How could I, of all people, have slept though this genocide?

Part II of this article will be published next week.

Rita Banerji is an author, photographer, and gender activist. She is the founder of The 50 Million Missing Campaign (www.50millionmissing.info), a global lobby that raises international awareness about the ongoing female genocide in India. Born and raised in India, Rita has also lived in the U.S. where she attended Mount Holyoke College (B.A.), and later The George Washington University. Her education and work has largely been in the environmental field, and many of her projects had a gender focus, including one with the grassroots organization, Chipko. She received awards and recognition for her work from The American Association for Women in Science, The Botanical Society of America, The Charles A. Dana Foundation, and The Howard Hughes Foundation. Her book Sex and Power: Defining History, Shaping Societies (Penguin Books, 2008), a historical study of the relationship between sex and power in India, and how it has led to the ongoing female genocide in India, was long-listed for The Vodaphone-Crossword Non- Fiction Book Award (India). Many of her articles published focus on issues of gender, for which she received The Apex Award for Magazine and Journal Writing (U.S.A.) in 2009. Her website is www.ritabanerji.com

Rita Banerji is an author, photographer, and gender activist. She is the founder of The 50 Million Missing Campaign (www.50millionmissing.info), a global lobby that raises international awareness about the ongoing female genocide in India. Born and raised in India, Rita has also lived in the U.S. where she attended Mount Holyoke College (B.A.), and later The George Washington University. Her education and work has largely been in the environmental field, and many of her projects had a gender focus, including one with the grassroots organization, Chipko. She received awards and recognition for her work from The American Association for Women in Science, The Botanical Society of America, The Charles A. Dana Foundation, and The Howard Hughes Foundation. Her book Sex and Power: Defining History, Shaping Societies (Penguin Books, 2008), a historical study of the relationship between sex and power in India, and how it has led to the ongoing female genocide in India, was long-listed for The Vodaphone-Crossword Non- Fiction Book Award (India). Many of her articles published focus on issues of gender, for which she received The Apex Award for Magazine and Journal Writing (U.S.A.) in 2009. Her website is www.ritabanerji.com

The views expressed by guest contributors to the “It’s a Girl” blog represent the opinion of the individual author who contributes the content and should not be interpreted as being endorsed or approved by Shadowline Films. We feature these contributions to foster dialogue and exchange on gendercide and invite our readership to join the discussion.