Gendercide and The West

Gendercide is the unreported tragedy of our age.

Gendercide is the unreported tragedy of our age.

I was one of those guilty of dismissing gendercide as an Asian problem. Surely, unwanted female foetuses were aborted there, in illegal clinics, not here. And surely unwanted daughters were killed there, in forgotten villages, not here. The egalitarian Shangri-La that is ‘The West’ would never allow unwanted daughters to be eliminated in this way. Surely? The shocking truth, I discovered, is that gendercide is a global tragedy.

An Oxford University study revealed that between 1995 and 2005, 1500 girls “disappeared” among Indian communities in England and Wales. Sex selective abortions are the only plausible explanation. If the study is correct, the figures mean that 1 in 10 extra girls, who should have been born according to normal birth statistics, were selectively aborted. Sex-selective abortions are illegal in the UK under the 1967 Abortion Act and yet, as the recent investigation carried out by The Telegraph exposed, families can and presumably have had pregnancies terminated here. Doctors, being secretly filmed, agreed to falsify paperwork to circumvent legal prohibitions even though they recognised the immorality of ‘female infanticide’. Sex-selective abortions are, shockingly, legal in the US and the post-communist states of east Europe all have unnatural discrepancies in their birth gender ratios.

Most, if not all, of the agreed solutions fall away when we understand gendercide as a global problem. Activists have always spoken of the need to economically empower women, to inform women of their rights and to improve legal enforcements. These are all the solutions to problems that don’t exist in the US, Australia or the UK. Those fighting to end gendercide have always kept faith in modernisation as a force that will uproot the “backward culture” of son-preference. But modernisation, though necessary, has been proved to be insufficient.

Gendercide is a problem of supply and demand. Modernisation has failed to root-out foetal gender-preference and developments in technology have facilitated femicide. With sex determination now possible at seven weeks online, new technologies have had the perverse effect of decreasing reproductive liberty rather than can increasing reproductive control. Logic suggests then, that the process of combatting gendercide must be inverted: eliminate supply before tackling demand. This though, might not be the answer either. Campaigners warn that those extreme enough to want a gender-selective abortion would “always a find a way”. As Kishwar Desai highlights, Indian families from the UK are prepared to travel to India to end pregnancies, where illegal abortions can be procured for a small price. It is impossible to know how many women each year go abroad to eliminate female foetuses. What is certain is that driving these abortions abroad or underground is counter to all interests.

It’s not only the absence of solutions that complicates the fight against gendercide in The West. Abortion – and controls on it – remains a fraught issue. The risk of talking about gendercide in The West is that it becomes engulfed by the abortion debate. The difficulty, as Cristina Odone notes, is that combatting gender-selective abortion ‘smacks of pro-life’. It is entirely consistent with being pro-choice to argue that gendercide is the not-too-remote consequence of permissive abortion controls. A hijacking of the anti-gendercide cause by either the pro-life or pro-choice lobby would be a huge setback.

Abortion and gendercide are distinct issues and if we are to end gendercide, we must constantly remind ourselves of this distinction. The routine elimination of female foetuses, solely because they are not male, is something we must all work to end.

Gendercide is an issue in relation to which our first and last question must always be: how do we end it? All manner of policy initiatives have been tried. Over concerns of sex-selection, the Council of Europe went as far as to suggest that doctors must now refuse to tell parents the gender of their baby. But technology and culture undermine policy at every stage and no legislation can combat a global cultural malaise. As Evan Grae Davis, It’s A Girl’s director has said, gendercide is one among many issues that is “greater than any single organisation can fight alone”. It is for this reason that the work of Shadowline Films, and similar projects, is vital: where policy falls short, awareness and activism must fill the gap.

Ram Mashru is a freelance political journalist. His writing interests encompass international affairs and human rights and he has written before on gendercide here. He is the founder and editor of Discuss[n], an online political magazine, and can be followed on twitter (@RamMashru).

Ram Mashru is a freelance political journalist. His writing interests encompass international affairs and human rights and he has written before on gendercide here. He is the founder and editor of Discuss[n], an online political magazine, and can be followed on twitter (@RamMashru).

The views expressed by guest contributors to the “It’s a Girl” blog represent the opinion of the individual author who contributes the content and should not be interpreted as being endorsed or approved by Shadowline Films. We feature these contributions to foster dialogue and exchange on gendercide and invite our readership to join the discussion.

How could I have slept though the annihilation of my own kind? How did I, an Indian woman, live on in such oblivion to the systematic and targeted elimination of millions of Indian women? Why did it evoke no response in me – no anxiety, no outrage, no resistance, no action? Not even involved thought! There is something so indescribable and bizarre about asking that question. I wonder if others belonging to groups that were targets of genocides have done the same?

How could I have slept though the annihilation of my own kind? How did I, an Indian woman, live on in such oblivion to the systematic and targeted elimination of millions of Indian women? Why did it evoke no response in me – no anxiety, no outrage, no resistance, no action? Not even involved thought! There is something so indescribable and bizarre about asking that question. I wonder if others belonging to groups that were targets of genocides have done the same? Secondly, I think that the manner in which this issue has been addressed, has completely dehumanized what is in reality a massive human-rights violation of a specific group of people. The ‘missing’ women and girls are referred to as numbers and ratios such that after some time one is not even aware that we are talking about human beings here and a gross infliction of violence against them. More so, there is an attempt to dismiss the role of the perpetrators – be it in the form of the legal system, culture and individuals, such that the way the world has come to view this is as they would news of an earthquake, or hurricane — something that just happens and cannot be controlled. So girls and women in India simply go “missing,” – not that a system comprised of individuals are deciding to and systematically targeting and massacring them.

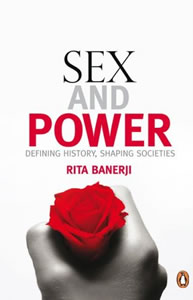

Secondly, I think that the manner in which this issue has been addressed, has completely dehumanized what is in reality a massive human-rights violation of a specific group of people. The ‘missing’ women and girls are referred to as numbers and ratios such that after some time one is not even aware that we are talking about human beings here and a gross infliction of violence against them. More so, there is an attempt to dismiss the role of the perpetrators – be it in the form of the legal system, culture and individuals, such that the way the world has come to view this is as they would news of an earthquake, or hurricane — something that just happens and cannot be controlled. So girls and women in India simply go “missing,” – not that a system comprised of individuals are deciding to and systematically targeting and massacring them. Rita Banerji is an author, photographer, and gender activist. She is the founder of The 50 Million Missing Campaign (

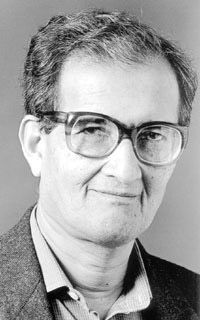

Rita Banerji is an author, photographer, and gender activist. She is the founder of The 50 Million Missing Campaign ( One of the incidents that my deliberation uncovered remains like a thorn in my soul, and I recount it here with much shame. It is an incident from my college days in the United States, and involves the Nobel Laureate, Dr. Amartya Sen, who had first used the term “missing” for the women who had been eliminated from India’s population. This is where the ‘Missing’ in my campaign’s title comes from. In 1986, Dr. Sen first raised the alarm on what his study revealed to be an abnormally high skewing of the normal, biological gender ratio in the populations of India and China. At that time

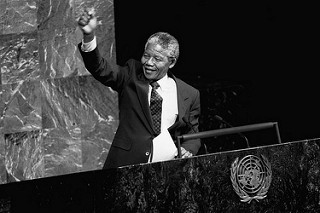

One of the incidents that my deliberation uncovered remains like a thorn in my soul, and I recount it here with much shame. It is an incident from my college days in the United States, and involves the Nobel Laureate, Dr. Amartya Sen, who had first used the term “missing” for the women who had been eliminated from India’s population. This is where the ‘Missing’ in my campaign’s title comes from. In 1986, Dr. Sen first raised the alarm on what his study revealed to be an abnormally high skewing of the normal, biological gender ratio in the populations of India and China. At that time  The ultimate irony of this story is that during this very time period, I was actually, actively involved in the student movement against South Africa’s apartheid government. Even before I had left India, at the age of 16, I had written an anti-apartheid poem that The Statesman newspaper in India had published. Soon after, I got my first passport and when I saw the stamp of the travel ban to South Africa on it, I had rejoiced that my government was not going to stand up for fascism. In college in the U.S., I eagerly attended talks by high-profile anti-apartheid leaders. I can still feel in my bones that highly charged energy and anger in the auditorium during a talk by

The ultimate irony of this story is that during this very time period, I was actually, actively involved in the student movement against South Africa’s apartheid government. Even before I had left India, at the age of 16, I had written an anti-apartheid poem that The Statesman newspaper in India had published. Soon after, I got my first passport and when I saw the stamp of the travel ban to South Africa on it, I had rejoiced that my government was not going to stand up for fascism. In college in the U.S., I eagerly attended talks by high-profile anti-apartheid leaders. I can still feel in my bones that highly charged energy and anger in the auditorium during a talk by  Rita Banerji is an author, photographer, and gender activist. She is the founder of The 50 Million Missing Campaign (

Rita Banerji is an author, photographer, and gender activist. She is the founder of The 50 Million Missing Campaign (